This is the final in our three-part series on implementing an action plan for aggressive carbon reduction targets, or as we call it: “ESG 2.0.”

If you missed it, check out Part I on getting buy-in from on-site teams and Part II on engaging tenants. As important as both of those initial steps are, at the end of the day, the human component can only go so far.

To make significant reductions, there will have to be improvements to the infrastructure on which buildings run.

These improvements fall into three broad categories:

- Conservation (eliminating waste in ongoing operations)

- Energy efficiency (improving baseline efficiency)

- Low carbon fuel selection (electrification)

This is nothing new. Owners and operators have been pitched continuously for a decade on the benefits of things like real-time monitoring, energy audits, demand response, and a host of high efficiency products.

The difference is that portfolios are now being forced to execute at scale. While successful pilots and case studies might make for great material in an annual ESG report, the strategy must be refined, systematized and expanded upon to move the needle on portfolio emissions.

The challenges

It is one thing to put out a report outlining ambitions for carbon neutrality, along with action items stating that the portfolio will “identify and implement operational improvements,” “install high efficiency HVAC equipment” and more.

The big question is “how.”

Many larger portfolios can’t even accurately answer how many buildings they own, let alone how many chillers are in those buildings, their age, expected replacement date or relative efficiency.

This lack of transparency is compounded by a common set of roadblocks:

- Monitoring utility meters alone has fallen flat because the data is limited to the building level and thus lacked the necessary level of granularity

- Pilots with automated HVAC solutions have not delivered results and created resentment among on-site engineers who feel excluded from being part of the solution.

- Energy audits have proven successful, only to have the gains reversed in 1-2 years as many small inefficiencies add up and performance “drifts”

- A data strategy focused on building management systems has meant that parts of the portfolio have necessarily been excluded

In some cases, owners and operators have felt “burned,” and have been turned off from testing and evaluating different solutions.

As such, both the technological issues and the emotional buy in will have to be addressed in order to achieve the aggressive targets being set forth.

Conservation

Go back 10 years and the cutting edge of energy management was digitizing the utility meters so sustainability teams could view their building’s consumption in real-time rather than waiting for the next round of utility bills.

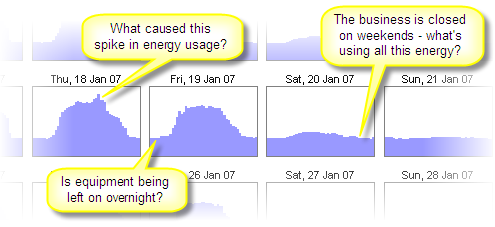

However, it eventually became evident that this strategy lacked actionability in two key ways. First, it did nothing to engage building engineers, who could do very little with the knowledge of how many kilowatts their building was consuming.

Second, it simply wasn’t granular enough. If there was a spike in consumption, it could mean that something was wrong somewhere, but the process of troubleshooting and root cause analysis was always a daunting proposition.

More recently, owners and operators have been pitched solutions that integrate with building management systems (BMS), constantly analyzing equipment-level and environmental data to make ongoing optimizations.

This proved successful, but generally could only be applied to office properties with a modern BMS. Moreover, solutions that automated decision making also tended to reduce operator buy in, which as we saw, is a necessary element in ESG 2.0.

To design a better approach, there needs to be a focus on flexibility of deployment strategy, as well as on integrating real-time monitoring into normal workflows rather than introducing a new (and often time consuming) process.

Flexibility of deployment strategy means using the data that’s available first and then capturing data as needed using sensors. The goal is to affordably monitor the critical energy loads; the specifics will necessarily depend on the infrastructure currently in place.

Once real-time data is flowing from critical equipment, conservation is most successful when the insights meet the operators where they are. Generally, that means integrating them into the same tool they use for managing work orders.

Sara Neff hit the nail on the head with this recent quote on the Nexus Podcast.

“A building can only run as efficiently as its engineer knows how to run it. Unless you have an engineer-first mindset, none of your energy efficiency efforts is ever really going to reap the rewards."

Energy Efficiency and Electrification

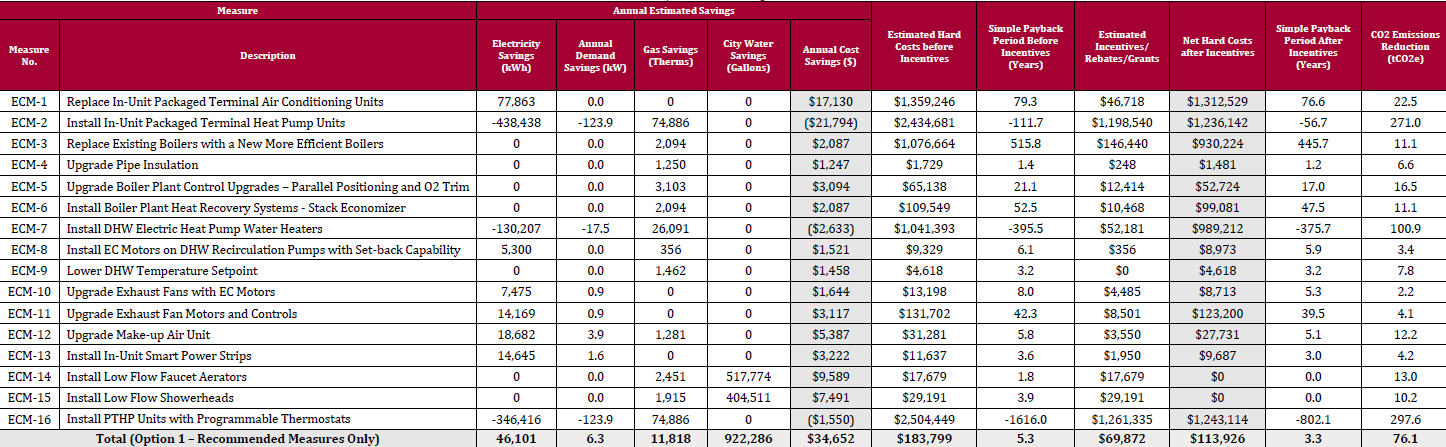

An ASHRAE Level II energy audit is the gold standard for the industry. The process is also well understood.

An owner will pay an energy service company or engineering firm to walk the building and deliver a report on how it can be “tuned up” as well as what capital investments could be made to reduce consumption with an attractive payback period.

There are two problems with relying on this approach as the basis of a carbon reduction plan, however.

The first is due to “performance drift.” After the tune up occurs, there is a tendency for the building to lose its new-found efficiency in the normal course of operations.

Over time, tenants request overtime HVAC and the schedule not being changed back, or because a fire alarm went off that reset the configurations of equipment, or any number of other normal circumstances.

With continuous commissioning, these small variances can be corrected for in real time, allowing the building to remain “tuned up” indefinitely.

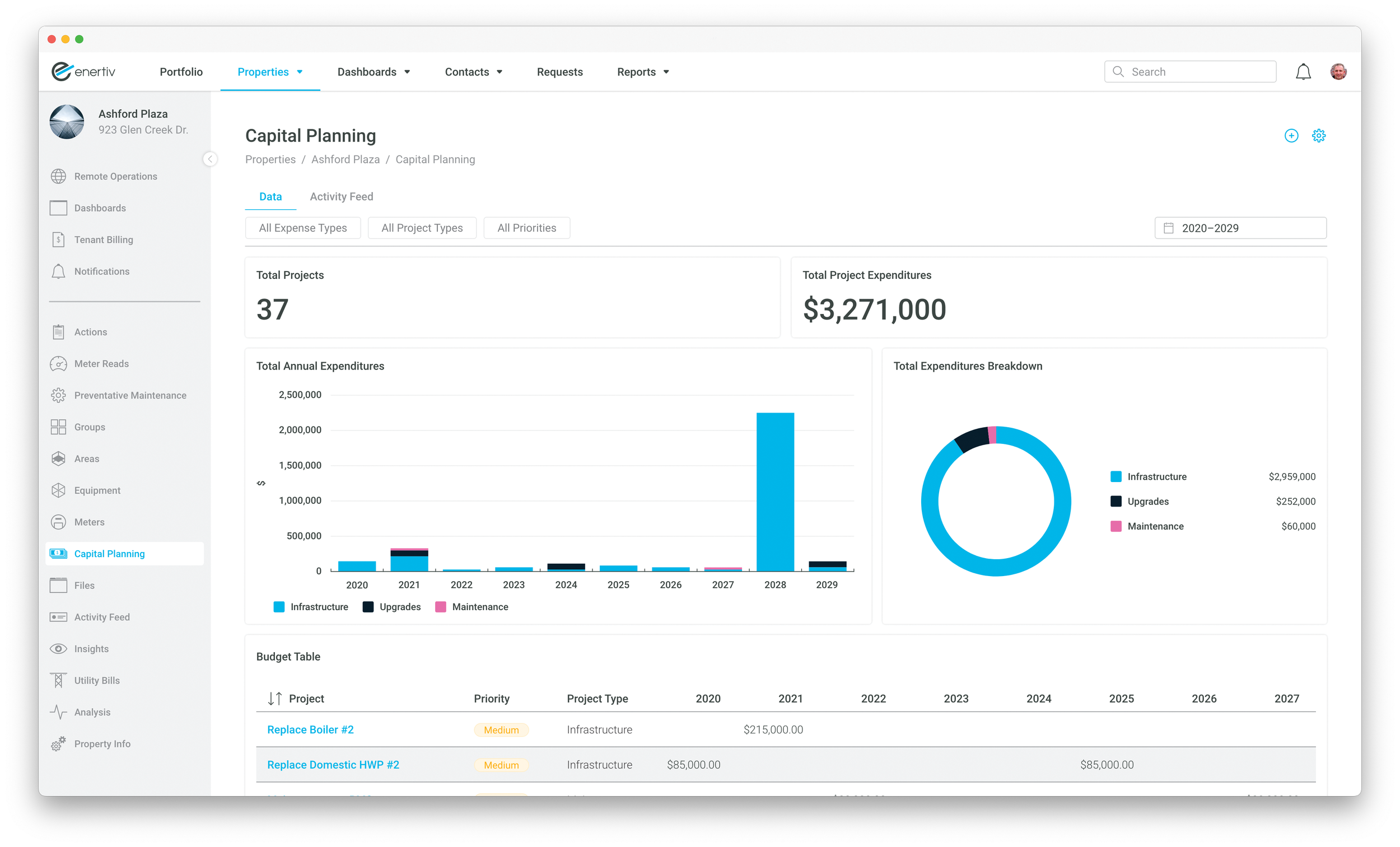

The other problem is that the retrofit and upgrade recommendations from the energy audit generally lives outside of the normal capital planning process.

In addition to the obvious challenges of integrating multiple budgets and competing priorities, this process often misses the potential for taking energy efficiency into account in all capital decisions.

Every budgeting season, equipment replacement decisions are being made with “in kind” systems. That means a direct replacement for what existed previously.

In order to hit aggressive carbon reduction targets, every single capital decision must be made through the lens of ESG 2.0. LED lighting must be installed, every new pump, chiller, fan and other HVAC equipment must be high efficiency, as well as the building envelope (windows, walls, roof, etc.).

Likewise, the only way that the world has figured out to decarbonize is to electrify everything. Capital plans must include plans for electric boilers, cogeneration systems, and distributed heat pumps.

The challenge is allocating capital. ESG cannot supersede normal fiduciary responsibility. Making investments like this requires a much greater level of transparency, in the form of software, where information can be sliced and diced and rolled up with ease.

Fortunately, the real-time monitoring used for conservation and continuous commissioning can also be aggregated, so that decisions can be made according to real world operating conditions.

This is something that 90-page energy audit reports simply cannot do.

Conclusion

Decarbonizing a commercial real estate portfolio is a daunting task.

Certainly, there are elements that are out of owner’s and operator’s control. For example, the portfolio could electrify everything and the grid could remain powered primarily by fossil fuels.

But there is a lot that can be done.

The first step is to engage operators by meeting them where they are. Give them tools that make their jobs easier before expecting them to go above and beyond for carbon reductions.

The second step is to engage tenants by taking full advantage of the built-in touchpoint created by the utility bill back and/or submetering process. Many tenants have their own ESG reporting requirements and are eager to partner, if the process is easy for them.

The final step is to monitoring all critical equipment through a flexible data approach that takes advantage of what’s there and affordably creates data when necessary.

This monitoring initially identifies operational improvements, ensures that performance doesn’t drift negatively over time, and arms owners and operators with the data needed to make informed decisions during the capital planning and budgeting process.

And in doing so, the portfolio becomes more competitive and resilient, both against climate policies from investors and regulators, and against rising operating and capital expenses.

.png)