Last week, we explored how integrating maintenance data into the capital planning process can lead to better outcomes in terms of deferring expenditures in a more systematic way.

With interest rates rising, that is becoming increasingly important. But equipment will have to be replaced at some point.

It can no longer be about getting the system that’s going to last the longest, or that the chief engineer is most familiar with.

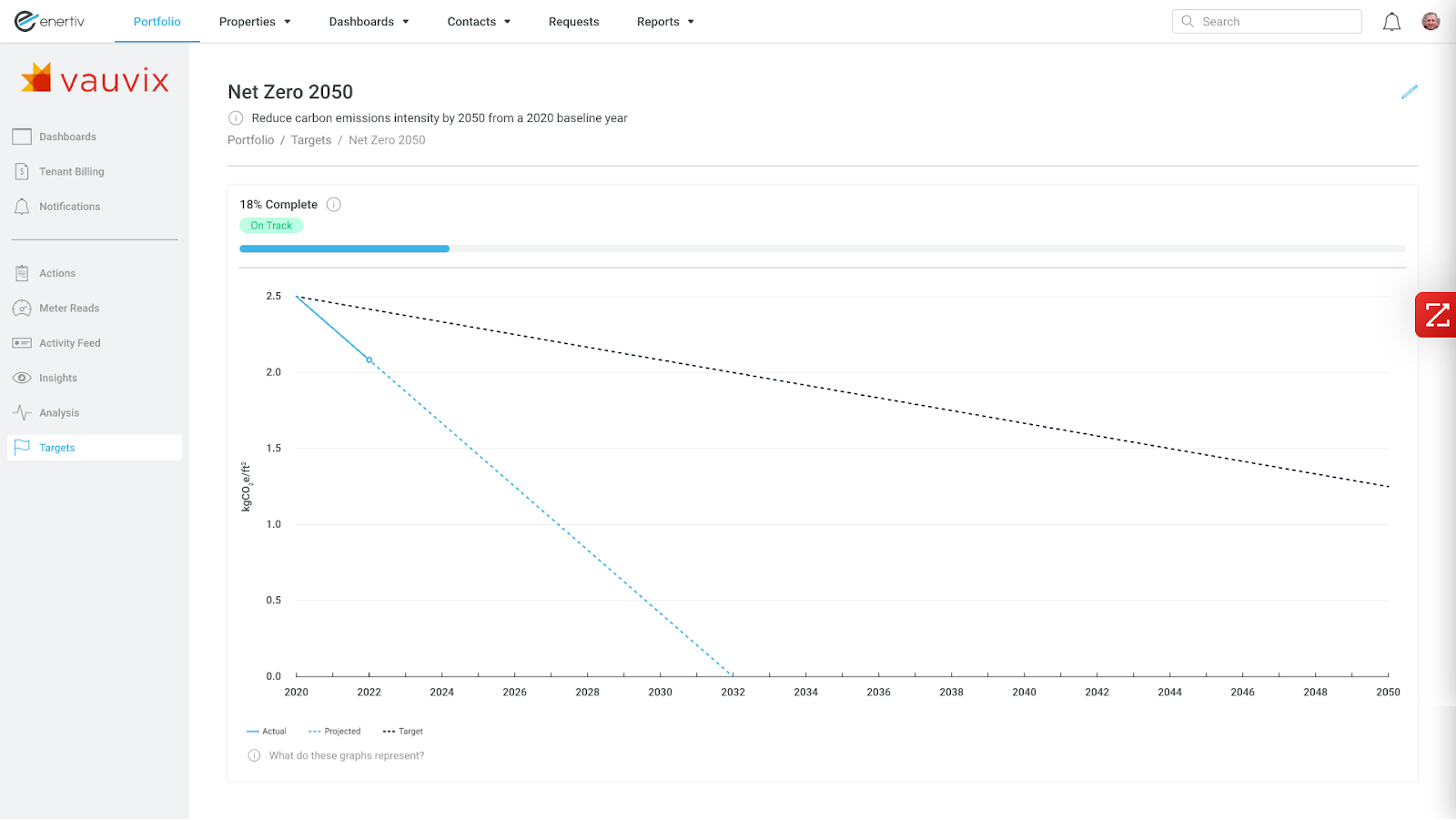

That’s because nearly every portfolio is under pressure to meet aggressive ESG goals. In fact, when all added up, it’s estimated that the industry will have to deploy $18 trillion to decarbonize their portfolios.

And just like building a new coal-fired power plant locks in a utility grid’s emissions for decades, so does every decision about boilers, air handling units, chillers, and other critical equipment. The wrong decisions could make achieving lofty targets out of reach, or completely reliant on increasingly expensive offsets.

At the same time, there are budget realities that must be considered. The cost of capital is going up and so each decision must be made prudently.

The problem with energy audits

For a long time, sustainability teams lived in a completely different universe than asset managers and engineering.

And yet, the methods deployed are similar. In the same way that a property condition assessment is performed to determine what needs to be fixed or repaired, sustainability teams traditionally start with energy audits to determine how to improve efficiency.

The output of an energy audit is tuning of control systems, a number of “low hanging fruit” items that can be knocked out quickly and affordably, and a laundry list of more capital intensive opportunities to improve efficiency.

Then, when budgeting season came around, sustainability was on the outside looking in, searching the portfolio to find available budget while having to constantly justify investments with ROI analyses.

But with the ESG pressures mentioned above, this is rapidly changing.

Here’s the rub: instead of simply changing relative authority, portfolios should be thinking through how to integrate the two worlds.

An integrated approach

What if, when normal equipment replacement decisions had to be made, sustainability goals were taken into account?

How might that look in practice?

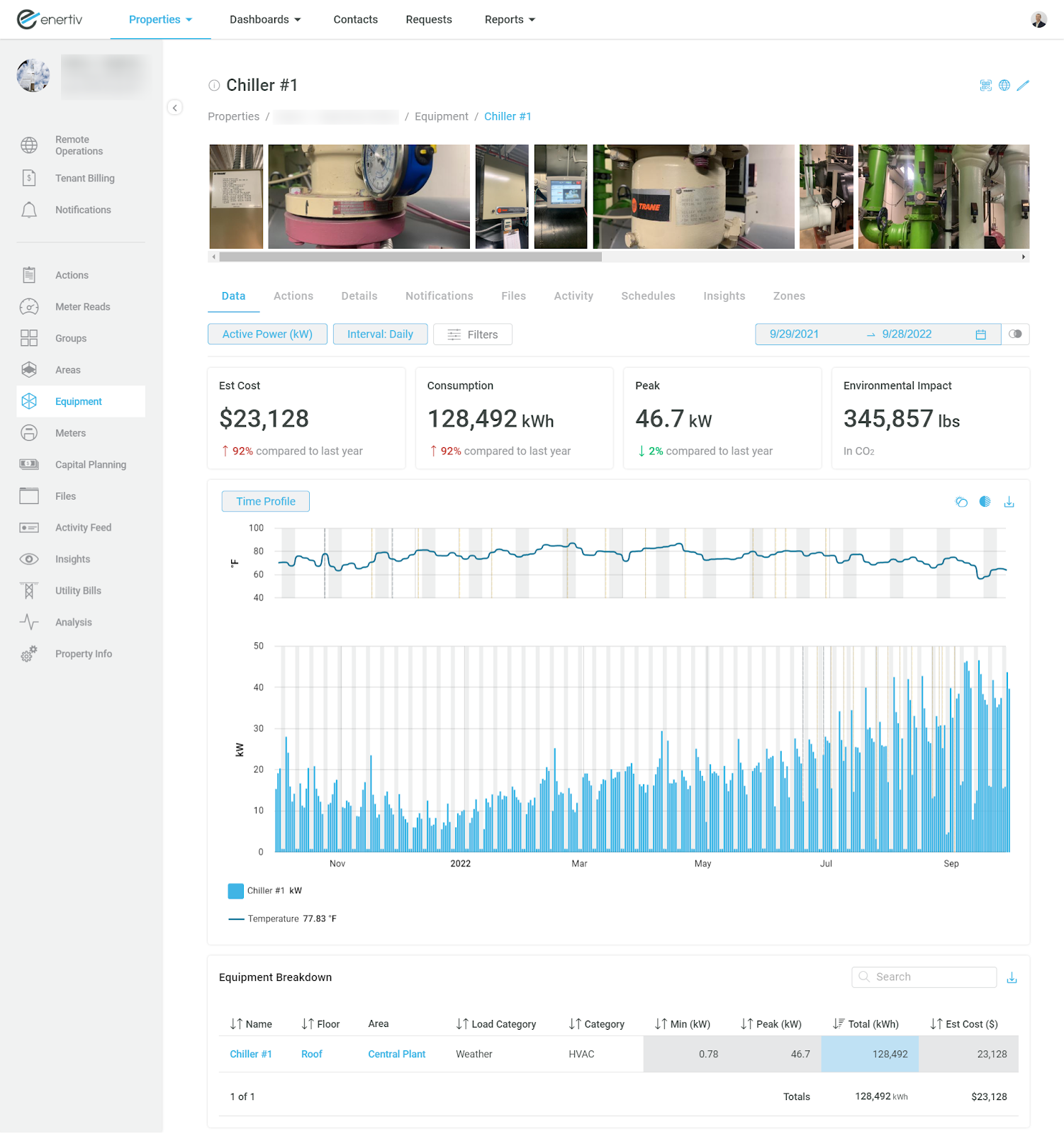

A good first step is to know the real-world cost and consumption of the equipment you’re replacing, as well as the efficiency of the potential replacement makes and models.

Then, with a little bit of calculations, you could see exactly how different decisions will impact your overall energy consumption.

One more step and you’d be able to overlay all of these decisions onto property and portfolio-level goals.

Going further

Of course, you may not want equipment replacement decisions alone to determine your capital investment strategy.

Real-time energy monitoring has been shown to deliver tremendous savings from optimizing what’s already in place (not to mention calculating runtime hours as mentioned in our previous article on capital planning).

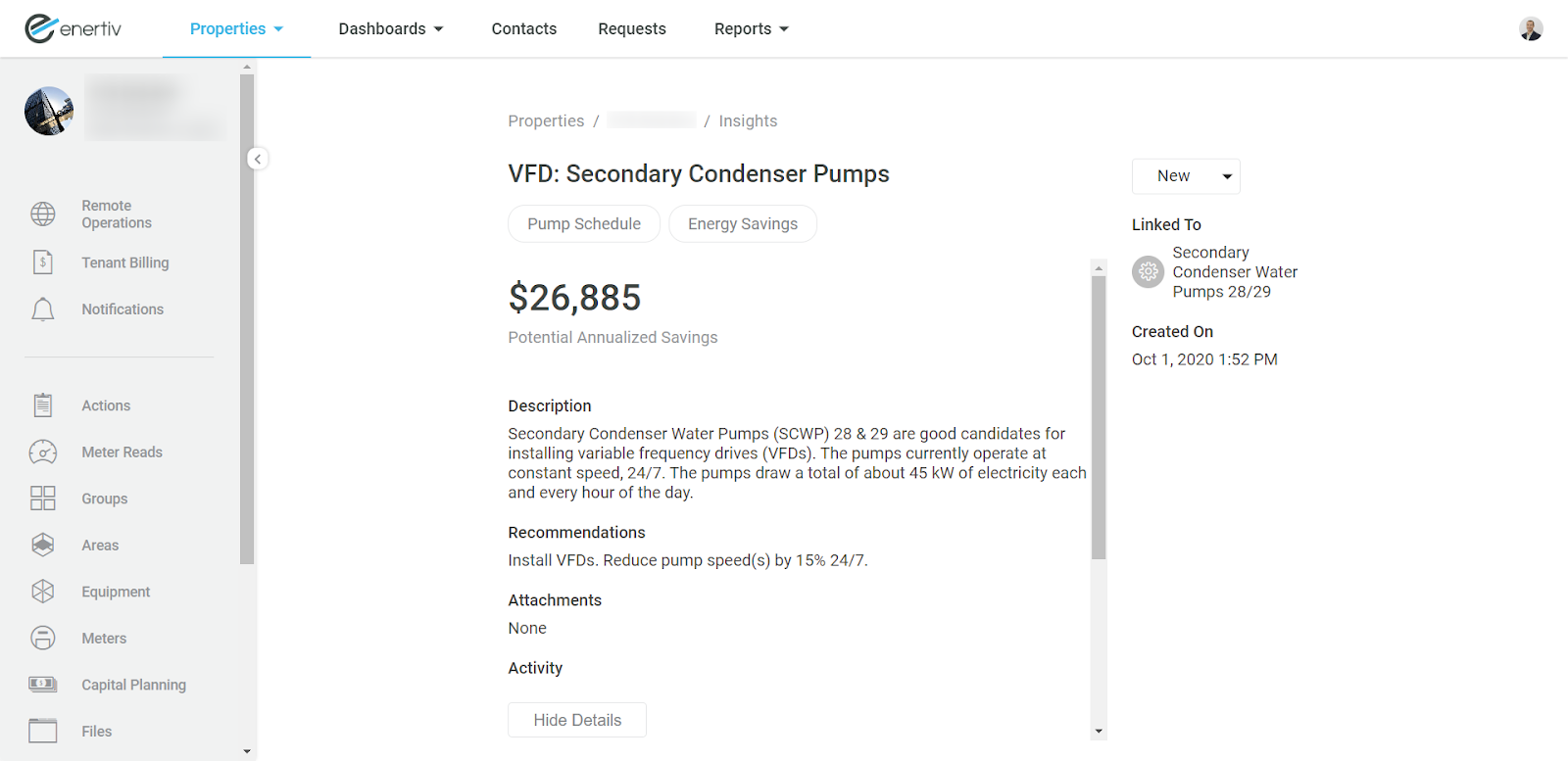

But what often gets overlooked is the ability to identify opportunities for retrofits and upgrades and to quantify exactly what the savings will be.

This is the concept of continuous commissioning, which is critical because of the well-documented phenomena of “performance drift,” where buildings become 20% less efficient only two years after an energy audit and retrocommissioning.

Not only does continuous commissioning help lock in optimizations for the long term, it provides the data to quantify the value of upgrades.

Unlike the potential items in an energy audit PDF. These can flow directly into the overall capital plan.

Conclusion

If we want to fix the capital planning process, we need a different strategy as it relates to energy and ESG.

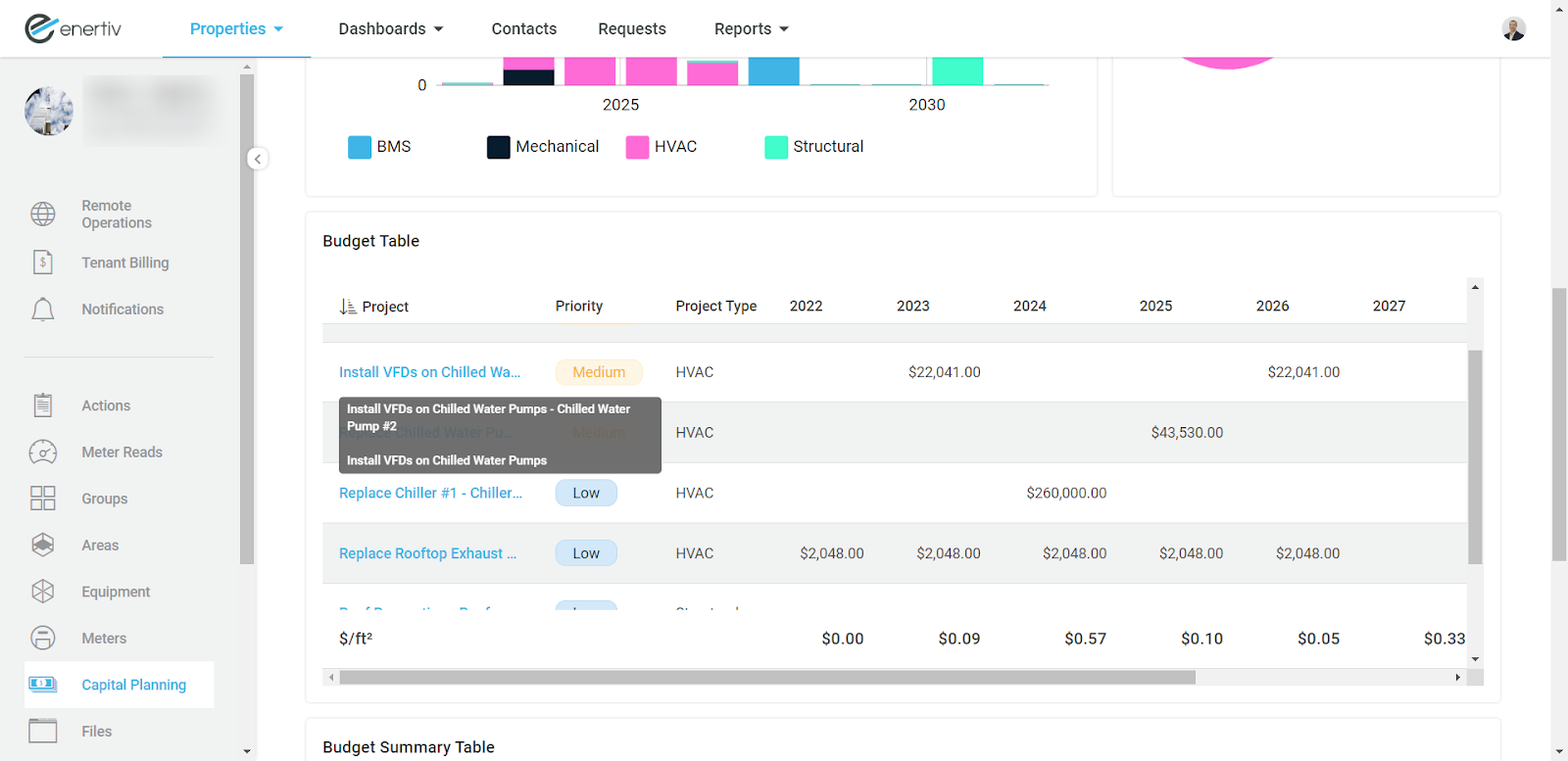

The point is not to throw out the existing workflows. Capital plans can be started with a traditional property condition assessment and refined over time with ongoing maintenance data.

Likewise, energy audits are a good starting point for determining the different options for reducing consumption, but these should be constantly refined with empirical, equipment-level data.

A modern capital planning process infuses normal workflows with sustainability goals, while at the same time ensuring that investments made for pure efficiency sake are integrated in the standard processes.

.png)