By now, everyone has heard the trope: smart building technology, driven by the internet of things and artificial intelligence, is poised to revolutionize the built environment by dynamically adjusting to occupant needs in an integrated and efficient fashion. Unfortunately, that string of words means almost nothing to the people in a position to invest in technology for commercial real estate portfolios.

When the jargon overload becomes too much, owners and asset managers ask the only sensible follow-up, what’s the direct return on investment? While the short-term economics are obviously critical, the lack of clarity about what smart building technology is (and isn’t) has led landlords to miss the big picture.

Technology is not a standalone investment, it’s a tool meant to be infused into every team, every process, and every decision. Smart building technology is no different; anything that can be integrated to improve the workflows necessary to operate buildings is another step towards “smart,” a process which has no defined end.

On the most fundamental level, whether through complex automation or by hand, buildings are operated by a series of workflows. The two goals these workflows are straightforward: to keep the building “working” for the tenants so they continue to pay rent and to limit the expenses paid by the landlord as much as possible.

Some buildings are designed from the ground up to incorporate more sophistication into these workflows. For example, The Edge developed by OVG Real Estate in Amsterdam, automatically finds tenants a workspace that fits with their calendar for the day, adjusting the light and temperature to match personal preferences.

The Edge may very well be the smartest building in the world, but that wouldn’t be due to the insane level of sophistication it displays. Sophistication and automation are expensive and simply get priced into the lease like anything else. The single tenant of The Edge, Deloitte, even admitted that their philosophy on the project was that anything with a return on investment of less than 10 years was worth a try. That is not a luxury many can afford.

The goal of smart building technology is not necessarily to add sophistication, it’s to identify and systematically eliminate the inefficiencies within the workflows in place, whatever those processes may be. This waste can be found everywhere, from equipment maintenance and repairs to tenant utility cost recovery, CapEx planning and forecasts, utility costs, vendor and staff management, due diligence, documentation storage, and more.

Turning Data into Action

Everyday, millions of Americans step on the scale to read their weight and use that number to understand their relative health. Unfortunately, in addition to only being a proxy for health, weight is a lagging indicator. It is not useful on a day-to-day level and by the time you get the information, it’s not actionable.

The same is true for building operators aiming to keep tenants happy while keeping costs down. In most cases, the only information to go off is what can be pulled by the building management system or energy management system. Like weight for personal health, this data is only a proxy for asset efficiency and is a lagging indicator, potentially interesting to review, but not actionable.

That is why smart building technology is often synonymous with building data, although they are two different things, one cannot work without the other. Granular building data can be derived from sensors placed at critical points in the electrical, mechanical and/or plumbing infrastructure as well as from digitized versions of the documentation that operators use to understand equipment such as nameplate information, operations and maintenance manuals, and riser diagrams.

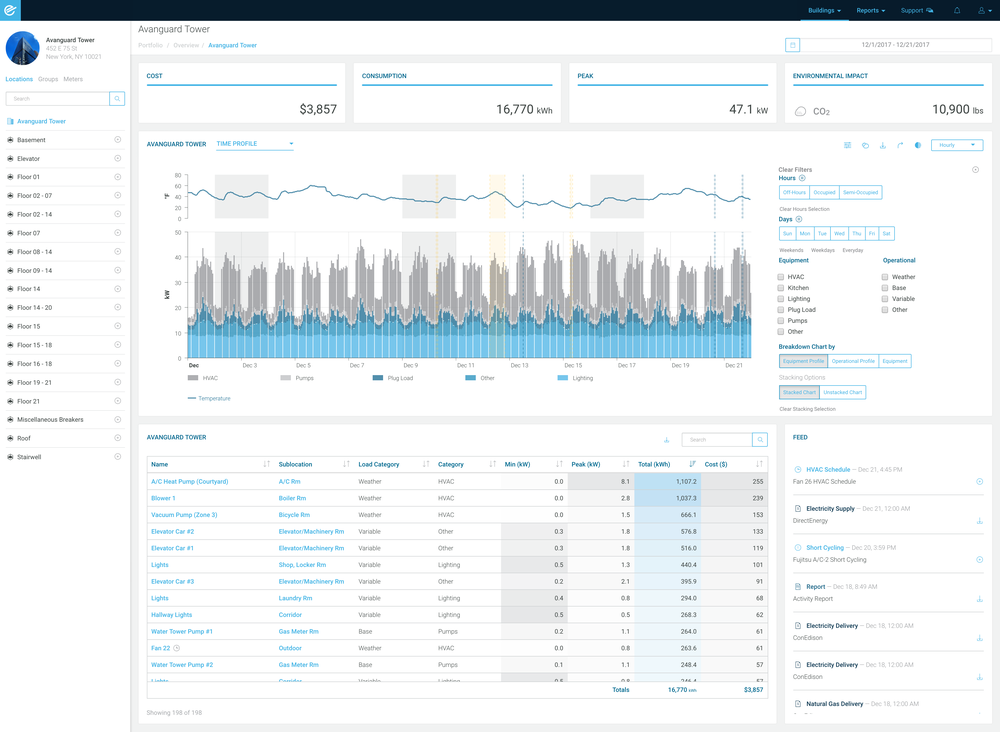

Generally, sensors are set up to capture data and send it wirelessly to a central database. This raw data is often visualized with charts and graphs, but this does not solve the lagging indicator issue. No matter how rich the dataset, it’s like an open book test, an operator would need to know where to look to find answers.

More importantly, the operator would have to be able to look. The work of a building operator is necessarily hands-on and largely occurs in the field. In addition, many operators are too busy to get to their routine tasks after handling the unexpected issues that occur throughout the day, let alone attempt to analyze unfamiliar datasets.

What are needed are “insights,” meaning specific recommendations sent to operators the moment a problem or potential efficiency is identified. The question is how the software being fed data from sensors could do this. It’s not enough to simply say “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence.” How is an owner or operator supposed to know which vendors’ machines are the most intelligent?

It’s not as complicated as it might seem. Let’s say you wanted a computer to be able to pick men out of a crowd and categorize their clothing. The way to do this is to simply show the computer ten million pictures of men in various kinds of clothes and it will eventually start to identify patterns. That’s really what is meant by machine learning. It’s not intelligence as much as the brute force of having ten million examples to choose from.

This is exactly why most building management systems, which also leverage granular data from equipment, are not necessarily “smart.” These systems never amass enough examples to determine patterns because the data is often kept on premises and is only stored for a few weeks. Smart building technology is different in that it learns from every piece of equipment across all the buildings it is installed in.

Patterns are Not Insights

With the knowledge that “artificial intelligence” is nothing more than access to a huge number of examples, owners can understand which vendors have the most “intelligent” machines by comparing the size of their datasets.

But that’s not the full story. Computers are smart enough to identify patterns and anomalies, but they’re not smart enough to know what those events “mean” without the help of humans.

The truth is that a boiler suddenly failing, and a boiler being shut down for routine maintenance, look indistinguishable in the raw data and therefore to computers. But to building operators, these events couldn’t be more different; one is a drop-everything-you’re-doing type of emergency, the other is nice to know.

This is where technology gets infused into the workflows already in place. The strengths and weaknesses of computers and humans perfectly complement each other. Computers can digest and categorize enormous amounts of data in the blink of an eye, but struggle with context. Humans are very slow at digesting data and forget previous learnings, but understanding context happens unconsciously.

Instead of sending a false positive alert that the boiler is down every time there’s maintenance, technology can be infused into the workflow. When maintenance is being performed, the building operator or third-party vendor can leverage a mobile app to tie their work to the specific boiler.

By combining a logged maintenance event with verification through sensor data, the landlord has effectively streamlined their maintenance and repair workflows, bridged the disconnect between on-site teams and management, and ensured that third-party maintenance vendors are being accountable to their contract. When the boiler shuts down unrelated to maintenance, operators will be notified and can be fully confident that the alert is real and urgent.

This streamlined process will produce the direct return on investment that owners are looking for. In 2018, maintenance and repairs passed utility expenses as the largest non-fixed operating expense line item in CRE. Much of these costs are wasted due to operators being unaware when (or if) maintenance has been performed and being reactive to equipment faults rather than proactive. In addition, in terms of bottom line cash flows, better maintenance extends the lifetime of equipment and thus lowers CapEx requirements.

But the value is not limited to direct return. The property has gotten “smarter” because it is working better for tenants by ensuring hot water is available and, in some unquantifiable way, encouraging them to renew their leases. In addition, owners and asset managers for the first time have transparency into what is happening in their assets, an intangible, but enormously valuable change from the status quo.

The magic of the technology described – sensors, managing an enormous database, pattern recognition algorithms, mobile apps – is that the costs are low and falling every year. Every building performs maintenance and repairs in some way or another. To this end, by leveraging the right technology, any building can become smart, not just ground-up developments with robust automation systems.

Conclusion

Smart building technology is not about the return on investment that can be achieved through recommendations on how to configure existing building management systems. It’s not even a standalone investment that should be evaluated based on simple payback periods.

Instead, it is something to infuse into the DNA of the organization and the fundamental tool to wield to evolve and improve every aspect of the organization. While smart building technology is based on cutting edge innovations in sensor technology and machine learning, the workflows that are being targeted are as old as building themselves.

Many of the problems faced in operating commercial real estate have no textbook solution. Landlords now have the opportunity to think through their business, their pain points, their tenant’s needs, and their physical assets and work with technology companies collaborate smart building technology that works, regardless of starting point.

Interested in seeing smart building tech in action? Schedule a demo of Enertiv’s Platform today!

CASE STUDY

Top 10 Global Asset Management Firm deploys Enertiv to get 100% utility data coverage across 100+ industrial sites

Light at the end of the tunnel

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve likely realized that implementing a utility data collection system in-house involves much more than installing meters and connecting APIs.

Yes, it’s possible to build it from scratch.

But it takes time, resources, and a learning curve that’s hard to fully anticipate.

Unless this is your core business, you’ll likely spend years learning lessons we’ve already paid for — through failed installs, messy integrations, and countless conversations with teams with real-world demands.

What may seem like a straightforward checklist today was, for us, a long path marked by challenges and meaningful breakthroughs.

Today’s sustainability leadership depends on speed and data precision. If you’re serious about hitting decarbonization targets, every delay in collecting accurate utility data is a missed opportunity.

That’s why going through this entire build process internally can actively slow your energy transition.

You don’t need to start from zero to reach net zero. You just need to avoid the mistakes that stall everyone else.

%20consider.webp)